Licence plate recognition with motion blur

Will CNNs still work well in such situations?

This project was done as part of URECA in AY16/17-17/18

Key contributions

- Created a dataset of licence plates with motion blur, containing 114,000 individual character crops

Motivation

OCR is pretty much a solved problem in computer vision and such tools are readily available (e.g. integrated into Mac’s Preview). However, there are several scenarios where it can still fail. One example would be the case of licence plate recognition, where cars could be swerving and travelling at high speed, resulting in only a blurred image being captured.

Would it be possible to train CNNs to recognise such blurred licence plates that are indiscernible to us? Let’s find out! 🔍

Existing work

There are definitely papers on OCR (e.g. MNIST) and even automatic licence plate recognition (ALPR), but at that point of time, most existing works worked on clear images (or at most with a bit of blur). There are image deblurring techniques available, but most require the estimation of a blurring kernel. This is difficult to generalise since such a kernel would vary significantly depending on the environment and recording medium (e.g. relative velocity, lighting, exposure length, etc.). Thus, we want to investigate whether an automated and generalisable approach can be achieved via deep learning.

Methods

Since there are no readily available datasets, we had to create one ourselves from scratch. Briefly, here’s how we did it:

- Record videos of moving vehicles

- We literally sat on top of a double deck bus, sat in front and used our phones to record vehicles in front of us.

- Extract frames from the videos via VLC

- Crop car plates from frames (at that time, this had to be done manually since automated methods did not work)

- Label crops (there are different kinds of car plates)

- e.g. 1 line vs 2 lines ; different combinations of numbers and letters

- some frames will have clear images and they can be used to guide the labelling process for blurred frames

- For each car plate configuration (e.g. 3-4-1, 1 line), identify the largest crop and ensure that it is straightened

- Perform affine transformation via MATLAB on the rest of the crops w.r.t the largest crop so that all crops will be aligned

- Crop out each character from the whole plate (again, this is manually done)

- Generate bounding boxes that captures about 80% of each character

- Resize the final crops to 30x30 pixels

End product: 36 folders of crops labelled A-Z, 0-9, amounting to 114,000 individual character crops. Some characters occur less frequently, e.g. M, U, V, W and numbers are generally more well and equally represented than letters.

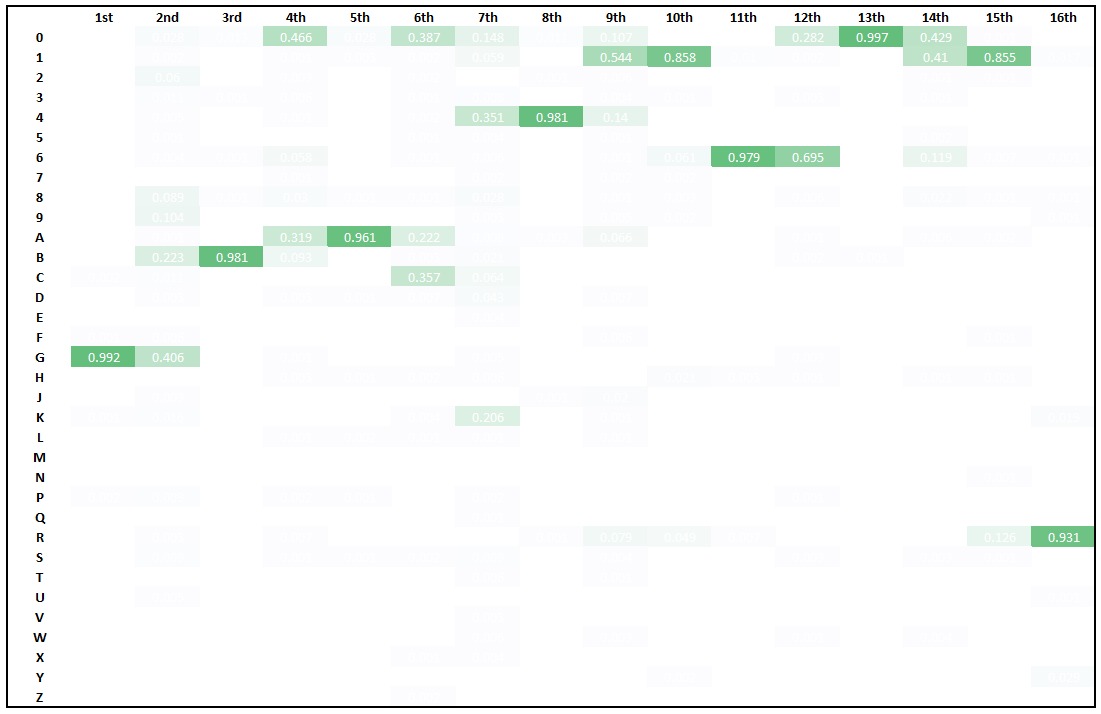

With this dataset, we can finally train a model to perform character recognition. We used a DenseNet (at that point, it was one of the SOTA) to perform the multi-class classification task (36 classes).

Results

Quite impressively, our model was able to achieve an accuracy of 99.6%, given individual character crops. On hindsight, this could potentially be inflated by data leakage (especially since this was our first deep learning project). For example, when splitting the dataset into train and test, we might not have directly done the split for each folder and did not make sure that characters from the same licence plate are not in both the train and test splits.

Future work

Even if the performance is still high after ensuring that data leakage did not happen, there are still a couple of steps left before a model can be deployed. The current model requires individual character crops, but it would be too troublesome to perform this manually for every frame that needs to be investigated. One way to address this problem is to design a system that takes in a car plate as input, produce individual crops by making small strides laterally across the car plate and generate a probability map of what character the CNN guesses for every crop.

There are some limitations in our dataset. For example, there are no ‘I’s and ‘O’s in the dataset as these letters are not used in vehicle license plates in Singapore, presumably to avoid confusing them with 0 and 1. Our dataset does consider images taken from different angles and lighting condition, but darker images are likely to be underrepresented and weather conditions (e.g. rain, cloud cover) were not thoroughly considered. Inclement weather would present a very challenging task (e.g. car plates covered by heavy rain, camera lens blurred by raindrops). Finally, the extent of motion blur might not be that great, partly due to the need to have some frames without blur. Future work would have to address these issues to produce a system that will work well in most situations.

Learning points

Manual data collection is extremely labourious and going through this process makes one very appreciative of open-source datasets. There are numerous decisions that have to be made along the way, e.g.

- Format to record the labels (we decided on

<Car plate number>_<Video file name>_<Type of car plate>_<Recording type>_<Lighting>_<Viewing angle>_<Car plate color>). - Best way to store the dataset. We learnt it the very, very hard way that HDDs are awful at transferring thousands of small images. Having SSDs would make our lives much easier.

Deep learning was beginning to get popular but was still at a rather nascent stage at that time (2016) and one of the popular frameworks then was Caffe. As freshmen, it was awfully hard to figure out how to even get it installed correctly (documentation was essentially non-existent for Windows, every line in the Makefile had to be checked carefully) and we only got it to work when Caffe 2 was released. Eventually, at a later stage, TensorFlow got popular but was still terribly hard to use as compared to what we have today (e.g. Keras, PyTorch, with extensive documentation). Looking back, I think it would have been better if we entered the field 1-2 years later. So much time was wasted to get the frameworks to work and at that time, few people knew how to get things to work. It is pretty amazing to see how far things have developed in 8 years (2016 to 2024).

Is it an invasion of privacy, or would the benefits (e.g. safer roads if road users are deterred by the knowledge that they will be caught) outweigh the cons? I think the answer would be pretty nuanced (e.g. there’s data involved that’s somewhat PII and there is no viable way to get consent, but on the other hand it’s also publically available information) but upon reflection, this experience has guided me towards other research topics. It is probably OK to do research on it and produce a tool that would be useful for law enforcement agencies, but the data would have to be handled carefully (e.g. we did not openly release the dataset).