Singlish sentiment analysis

Can BERT perform polarity detection on text with code-switching?

This project was done individually for CE7455 in AY19/20.

Key contributions

- Collated 60,000 English-Chinese code-mixed utterances (likely the largest at that time, perhaps it still is?)

- Designed an automated labelling approach for polarity scores of code-mixed utterances (with bilingual negation detection)

- Showed that the use of multi-lingual pretrained BERT embeddings led to the best performance

Motivation

Sentiment analysis has been thoroughly researched for commonly spoken languages such as English and Chinese. However, real-life conversations in bilingual / multilingual communities are often code-mixed and different languages could be used to communicate different sentiments.

One particularly interesting and relatable example is Singlish, an English-based creole language which has an interesting mix of languages (Chinese, Malay, Tamil, etc.) and dialects (Cantonese, Hokkien, Teochew, etc.) due to our multicultural mix. The use of very nuanced discourse particles makes it even more colourful (and more difficult for any AI tool to interpret). Here’s one example from the SEAME dataset:

additional cost lah so 他们不会相信你讲的东西是 workable 的

A model trained on English would not have picked up the negative sentiment in the Chinese text. In fact, the use of lah in this context could even be interpreted as negative (impatience) and a model without exposure to Singlish would not have gotten it right either.

Would existing polarity detection models work well on Singlish? Intuition suggests that it won’t, but let’s find out! 🔍

Existing work

At that time (~2020), there has been an existing study on polarity detection from Singlish text. However, they relied on a hybrid model that combines an SVM classifier with a manually curated knowledge base of sentic patterns. Let’s see if deep learning tools would work better!

Methods

Before thinking about the modelling approach, we first need to construct the dataset. In fact, the process of constructing a code-mixed is not trivial at all (especially for an individual effort).

Collate existing datasets

After a thorough search, 5 relevant datasets were found:

- National Speech Corpus: around 1 million lines stored in the

TextGridformat, from conversations with code-mixing - NUS SMS Corpus: around 30k English and 30k Chinese SMS messages from Singaporean university students

- SEAME: around 10,000 lines of text with code-mixing (a mix of English and Chinese dominant lines)

- Singapore Bilingual Corpus: around 50,000 lines stored in the

CHILDESformat and parsed by thePyLangAcqlibrary - Malaya dataset: around 19 million sentences crawled from local online forums

Data cleaning

In short, common data cleaning steps include:

- Removal of irrelevant utterances (e.g. duplicated messages, mass SMSes, advertisements containing links)

- Removal of emoticons and punctuations (but stemming was not performed)

- Removal of linguistic annotations (from the NSC and SBC dataset).

Sieving out code-mixed utterances

Not all utterances are code-mixed and further preprocessing was done via regular expressions to identify utterances containing both English and Chinese characters. This leads to around 60,000 utterances remaining. While being rather small, this dataset is guaranteed to have code-mixing in every utterance.

Preparing mono-lingual baselines

Besides using the code-mixed data, we want to compare against mono-lingual baselines as well. There are a bit more nuances involved and the final dataset includes various versions:

- English only

- English + Pinyin (transliterated from Chinese characters)

- Chinese only

- Chinese only, segmented by

Jieba - Mixed (English and Chinese characters)

Data labelling

This is the most crucial part of the data preparation process. All the datasets did not come along with polarity scores. Since the processed dataset is stil too large to label manually, an automated and ensemble-based approach was used to assign the polarity scores. In short, this entails:

- Separating the English and Chinese portions of an utterance

- Using

VADERandSenticNet5(which has a Singlish version!) to score the English portions - Giving

VADERgreater weighting whenSenticNet5has few matches - Using

Jiebato segment the Chinese characters - Using

Jiaguand ChineseSenticNetto score the Chinese portions

More information about SenticNet can be found here.

Negation detection is critical for accurate labelling of polarity scores. This is taken care of using a customised multi-lingual negation detection algorithm that considers (i) Not-negators (e.g. didn’t, aren’t), (ii) N-negators (e.g. never, few), (iii) Chinese negators (不, 没), (iv) cases with commas, (v) un-negators (e.g. but, yet).

After the polarity scores are computed for each utterance, class labels are assigned based on an empirically derived threshold: polarity scores above 0.1 are labelled ‘positive’, scores below -0.1 are labelled ‘negative’ and the remaining scores are labelled ‘neutral’. The thresholds were arrived at by maximising the Cohen‘s kappa score (i.e. inter-rater reliability) between the assigned scores and human annotation of 300 sample utterances from the dataset.

With κ=0.61, the final dataset has 26,825 positive, 18,772 neutral and 17,517 negative utterances.

Results

At this point, I was left with little time to submit the project. Thus, the experiments done were more of a benchmarking analysis rather than creating novel architectures.

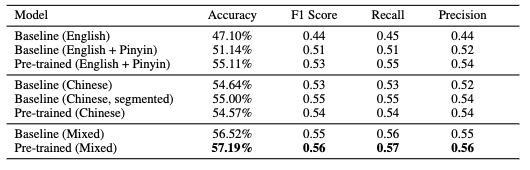

2 main approaches were attempted: (i) baseline models involved an embedding layer, Bi-GRU layer followed by softmax ; these models were trained from scratch, (ii) pre-trained models which replaced the embedding layer from BERT (uncased_L-12_H-768_A-12 was used for English, chinese_L-12_H-768_A-12 was used for Chinese and multi_cased_L-12_H-768_A-12 was used for Mixed).

Here is a summary of the results!

In sum,

- Pre-trained multi-lingual embeddings gave the best performance of 57.19% on a 3-class polarity detection task (positive, neutral, negative).

- Ablation studies performed by training the models with different inputs (English, Chinese, Mixed) showed that removal of Chinese words lead to a 9% decrease in accuracy

- Removing English words only led to a <2% fall, suggesting that Chinese could play a greater role in the expression of emotive content in Singlish text

Future work

60,000 utterances is still quite a small dataset for NLP. Attempts were made to increase this number. For instance, it is common for Chinese characters to be written in pinyin, i.e. Chinese characters transliterated to English characters. For some reason, I didn’t think about using a pinyin database to perform the matching (took another approach that did not work). That is definitely feasible (build a trie and the matching can be done in seconds). However, there’s a need to consider Mandarin terms unique to Singapore. There’s a database but it does not seem to be available as a CSV, so it would have to be scraped (or email them).

Another clear limitation is that only English and Chinese was considered in this study. A complete solution would have to involve labelling the utterances in Malay and Tamil as well (which is beyond my current abilities, i.e. tak boleh). Discourse particles and borrowed words were not fully considered in this study too.

Learning points

I didn’t get as much time as I wanted to develop the model, but some problems require a lot more time to get the pre-modelling steps done properly (i.e. constructing a good code-mixed dataset). There’s still quite a bit more work to improve model performance but a cursory look at existing papers performing 3-class polarity detection tasks shows that most get similar results (40%-70%). One common issue faced is that the dataset sizes are small (10k-20k) and manually labelled. So there’s likely more mileage to gain from improving the dataset first before trying to think of architectural improvements.

Source code

This repo contains a subset of the most relevant data and code. Feel free to send me an email if you need more information / files for your project. :)